December 15, 2016. When the vital signs of my then 27-month-old son, Thomas, dropped dangerously low and his eyes rolled back into his head, I burst into tears. I thought my baby was going to die. The ER pediatrician saw how upset I was. As she was instructing the staff to transfer Thomas to another floor to start an antibiotic drip, she pointed to his toe and asked me, “How long has he had this?”

A few days earlier, Thomas said he had a “booboo” on his foot. But no matter how hard we looked, we couldn’t spot anything. Maybe he stubbed his toe scampering around the house? We could see no signs of injury or swelling of any kind.

The next day, he had a fever. I gave him some Tylenol and fell asleep lying down beside him. I woke up with a start when he threw up all over me. We thought it might be food poisoning. The nurse at the other end of the Info-Santé hotline confirmed our suspicions when I described his symptoms. The following day, I took Thomas to see our pediatrician, who said he had come down with a particularly nasty strain of stomach flu that was going around.

That evening, he developed a red, blotchy rash all over his body. He was still feverish and very lethargic. My partner, Mélanie, suggested we go to the hospital. I said we should give him Benadryl and wait until the next day. She insisted: “There’s something wrong.” So off we went to Sainte-Justine.

By the time we got to the ER, Thomas was screaming his head off, something the triage nurse noted with concern. He refused to put a hospital gown on. In fact, he shrieked every time somebody touched him. They drew some blood and we waited (and waited!) for the results in an observation room.

As we approached the wee hours of the morning, there were dramatic changes to Thomas’s toe: it started to turn purple, the nail was pushed outward, and his entire foot had ballooned up.

As we approached the wee hours of the morning, there were dramatic changes to Thomas’s toe: it started to turn purple, the nail was pushed outward, and his entire foot had ballooned up. An ER physician rushed in, ordered a culture on his toe and admitted him to a room upstairs. Mélanie, who was on her way back from the cafeteria, was convinced it was flesh-eating disease. Shortly after that, Thomas lost all colour in his face. His arms went completely limp. Another pediatrician came in and ordered a course of three powerful antibiotics. Seeing my eyes well up, she said, “Don’t worry. Your son is in good hands.” I’m not sure why, but I believed her.

That first day, one specialist after another came to examine my son: an immunologist, a plastic surgeon, and the list goes on. While he was being pumped full of broad-spectrum antibiotics, they were all trying to figure out what was wrong with him,. His vitals were weak. He wasn’t passing any urine. His kidneys were blocked.

If we had lived farther away or waited until the next day to check in to the hospital, Thomas probably wouldn’t have made it.

Three days later, once all the test results were in, the verdict was finally handed down: staphylococcus aureus. To make a long story short, if we had lived farther away or waited until the next day to check in to the hospital (as I had suggested), Thomas probably wouldn’t have made it.

Mélanie wasn’t too far off the mark: his staph infection was similar to flesh-eating bacteria, except that flesh-eating bacteria kills tissue, and what our son had was trying to kill him.

I slept with Thomas in his hospital bed for a week. Once he was on the right antibiotics, he gradually began getting his strength back. I saw first-hand just how devoted the nursing and medical personnel were. I saw them regularly pull double shifts when they were short-staffed (I know that’s a whole other story, but overtime isn’t meant to be a regular thing—there, now I’ll put away my soap box). We owe a debt of gratitude to everyone there, especially Dr. Alix-Séguin, for turning things around. And thank you also to Nicolas Gagnon, the nurse who comforted us when we needed it most.

When Thomas was discharged on Christmas Eve, I sent a case of champagne to his caregivers to express our gratitude. I figured it must be disheartening to work on Christmas Day. One of them wrote back to me on Messenger: “Thank you for the bubbly, Mr. Lepage. It’s very generous of you. But, really, all we did was our job—the same as we do every day with all our young patients.” That’s when I understood that, for them, their work is more of a calling than anything else, and December 25 is a day like any other.

That’s when I understood that, for them, their work is more of a calling than anything else, and December 25 is a day like any other.

May 28, 2017. Back to the ER. Thomas had a high fever and had broken out into (another!) rash. Once again, Mélanie rushed him to Sainte-Justine. They gave him Tylenol and Advil, and in no time, he was bouncing around like the Energizer bunny. We were sent home. But once the effects of the medicine wore off, his symptoms flared up again. Clearly, something was amiss. So we returned to the ER. The same emergency physician, Dr. Alix-Séguin, was there. She told us to come back to the day clinic the next day.

She was worried enough that she admitted Thomas to the hospital for observation. It turned out he had contracted Kawasaki disease, which, left untreated, could have lead to coronary artery aneurysms and permanent heart damage. He needed immunoglobulin therapy, which would take about 12 hours to administer. There was a slim chance he would have a reaction, but we were told it only occurred in rare cases. Unfortunately, Thomas was one of those cases: he had a seizure that night. It was so violent that, yet again, we feared for his life. They stopped the treatment and started another preventive drug before resuming his therapy. His stay at the hospital lasted longer than expected, but the treatment eventually did what it was supposed to do, and Thomas’s condition slowly began to improve.

This time, we were in another wing of the hospital, but I witnessed the same dedication, the same professionalism and the same humanity as the first time around.

and the same humanity as the first time around.

This time, we were in another wing of the hospital, but I witnessed the same dedication, the same professionalism and the same humanity as the first time around. Our first nurse, Nicolas, even dropped by to check in on us after his shift was over after he heard Thomas had been readmitted.

Seeing as Thomas’s case of Kawasaki disease was “less serious” (the condition doesn’t claim as many lives, and deaths are generally limited to untreated patients in their teens), I took advantage of our second stay at the hospital to stroll through the corridors with Thomas once he felt up to it. As he trotted along next to me, I noticed that all of the young patients were getting the same attentive care as he was. It was as touching as it was reassuring.

A child who goes into septic shock after a case of cellulitis caused by a staph infection and then comes down with Kawasaki disease six months later, with no connection between the two, is statistically so rare that it makes winning the 6/49 look like a sure bet. Mélanie and I haven’t gone out and bought lottery tickets or anything, but we definitely did win the jackpot: our son is alive and healthy today—all thanks to the medical professionals at Sainte-Justine.

Mélanie and I haven’t gone out and bought lottery tickets or anything, but we definitely did win the jackpot: our son is alive and healthy today—all thanks to the medical professionals at Sainte-Justine.

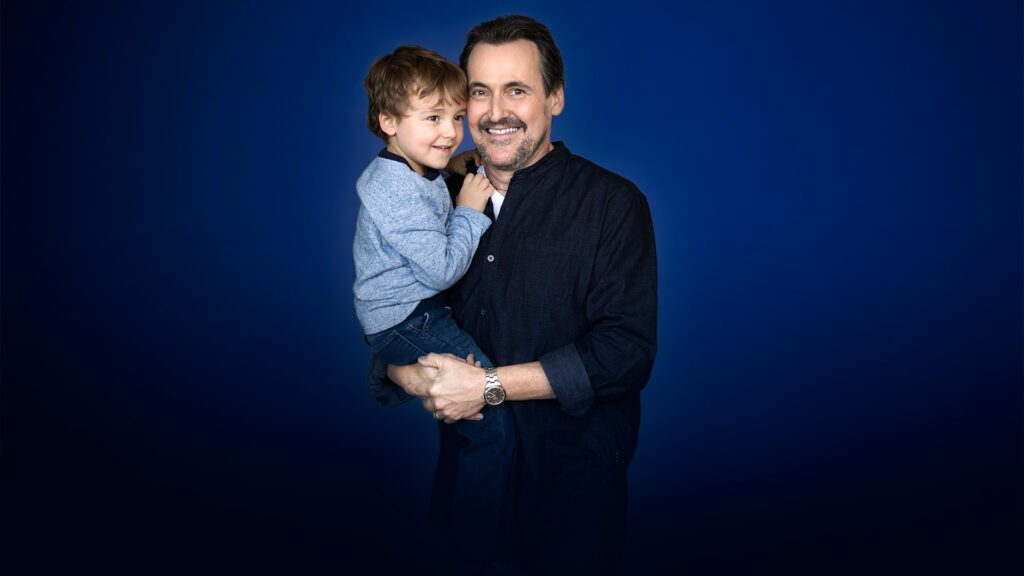

It may not seem like much for Sainte-Justine, but for us, it means the world. It’s thanks to them that I can hold my son in my arms. I’m extremely proud to be an ambassador for the CHU Sainte-Justine Foundation.

This is my way of giving back to the institution that has done so much for my family. And just like them, my love for children is contagious. So I’ll do my part to make sure others catch it too!

*The remarks expressed in this article reflect the opinion solely of the author and should not be considered as representative of the CHU Sainte-Justine Foundation.